The car might have been an Oldsmobile. Or maybe a Pontiac 6000. Maybe light blue, maybe gray. Whatever the car looked like to the only human being alive capable of describing it, police never found it.

In the middle of the night, in the middle of an intersection on the East Side, in the middle of the darkness, a man emerged from a car with a revolver. The gun was definitely gray— the witness seemed certain of that in her interviews with police. It had a long and skinny barrel and a round cylinder, she told police, but the detectives never found this, either. The man holding the gun stood at about 5-foot-8 or 5-foot-9, she thought. He was about 25 years old, black skin, light beard with a goatee, roughly 250 pounds. He had pimples on his face, she said in her sworn statement.

![Scene of the Crime[ID=5839187] ID=5839187](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/4044b1e7645488621f157de466cf1a990870caa2/r=500x333/local/-/media/WGRZ/GenericImages/2014/02/26/1393443242000-Crime-scene.jpg) It was May 26, 1997. Memorial Day. About 4:30 in the morning, following a long night out at the clubs. At the corner of East Delevan and Chelsea Place, a man walked toward her red Alfa Romeo and approached the passenger's side window, where the witness was sitting. Her best friend, Tomika Means, was in the driver's seat. After a few choice words, the man drew the revolver, pointed it at Means and shot her in the face. She died the next day. Prosecutors said the killer was merely experiencing a fit of road rage, looking for payback after a near-accident on the streets a few blocks back. It was a matter of seconds, the witness later testified under oath. But she believed she knew what she saw that morning, and more importantly, she believed without hesitation that she knew who she saw that morning with a gun in his hand.

It was May 26, 1997. Memorial Day. About 4:30 in the morning, following a long night out at the clubs. At the corner of East Delevan and Chelsea Place, a man walked toward her red Alfa Romeo and approached the passenger's side window, where the witness was sitting. Her best friend, Tomika Means, was in the driver's seat. After a few choice words, the man drew the revolver, pointed it at Means and shot her in the face. She died the next day. Prosecutors said the killer was merely experiencing a fit of road rage, looking for payback after a near-accident on the streets a few blocks back. It was a matter of seconds, the witness later testified under oath. But she believed she knew what she saw that morning, and more importantly, she believed without hesitation that she knew who she saw that morning with a gun in his hand.

In a case without physical evidence, her words put a man in prison for second-degree murder. 2 On Your Side has chosen not to name this witness and was unable to locate her for this story. Her listed address and phone number appear to have changed, but according to a private investigator who spoke with the witness two years ago, her confidence in the identification has not wavered.

She believes she saw a man named Cory Epps on the morning of May 26, 1997, which led to an arrest, an indictment and eventually a conviction. Epps is serving 25-to-life in the Attica Correctional Facility. He was 26 years old when police arrested him. Now, he's middle-aged.

Two decades later, legal experts are questioning the merit of the eyewitness identification. The Exoneration Initiative, a New York City-based non-profit that focuses specifically on non-DNA cases and wrongful convictions, first learned of Epps' case from a jailhouse letter.

"Memory is a funny thing," said Rebecca Freedman, the Assistant Director of the Exoneration Initiative. "Cory is undoubtedly innocent."

THE INVESTIGATION

Just as they never found the shooter's gun or his car, detectives also never found his matching fingerprints. The man who murdered Tomika Means left behind no physical evidence, meaning the key to the Buffalo Police Department's investigation rested with Means' best friend and her recollection of the crime from the passenger's seat. Police showed her the faces of possible suspects on the morning of the murder, but she said with absolute positivity that not one of them was the man she saw.

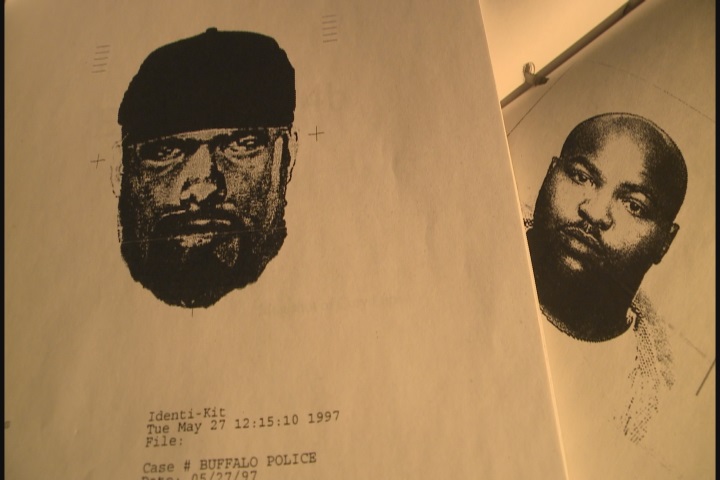

The next day, on May 27, she worked with police to create a composite sketch based on her memory.

More than a month passed. Means' murder remained unsolved. And then, suddenly, it dawned upon a relative of the victim that the sketch reminded her of somebody. She told police it looked like Cory Epps, a 26-year-old former Riverside High School student. Based on this tip, police took a picture of Epps and placed it in a photo array to show to the witness on July 7, 1997.

Epps did not have pimples, and he was about 6-foot-2, but he roughly fit the description of that composite sketch from a month earlier. The witness had told police on the morning of the murder that she'd seen the shooter around town, but she didn't know him personally. And when she saw Cory Epps in the photo array, something clicked.

"That's him," she told the detective, according to police records obtained by 2 On Your Side through a Freedom of Information request. "That's the guy who shot Tomika. I swear to God that's him."

The detective knew who Epps was too. He told her his name after she identified him. She told the detective she'd heard of Cory Epps. Police then drove to Epps' home, took him back to the station, asked him where he was six weeks earlier on Memorial Day and asked him if he killed Tomika Means. No, he said. They asked him why someone would pick him out of a photo array. 'It's a mystery to me. I don't know. This [expletive] is really crazy.'

They asked him if he would stand in a lineup to clear his name. Yes, I will. So a few weeks later, on July 30, 1997, he stood in a lineup. The witness again picked him out. Twice. Police had their evidence; the prosecution had its case. He was arrested immediately, then indicted.

On April 24, 1998, a jury convicted him based on the testimony of the lone eyewitness, even in the absence of physical evidence. When Judge Joseph McCarthy sentenced Epps in June of 1998, he stated in court that "eyewitness testimony, in and of itself, is not the most satisfying of evidence that can be received in the courtroom."

Epps has long maintained his innocence. I just don't understand, Your Honor, he said during his sentencing. I look like a description so they slap me in a photo array, I get picked. What can I do? What can anybody do? They find you guilty about something because I look like a picture.

"I know what you're saying, I hear you," Judge McCarthy responded. "The only thing I can say on behalf of the court is that you were represented by an able lawyer, that there was full due process within the perception of due process before a jury of twelve."

Two decades later, on a chilly morning in late January, Epps walked into the visiting room of the Attica Correctional Facility in his green prison jumpsuit. His three children are grown. He's a grandfather now.

"I've been waiting a long time to tell my story," Epps said. "I've been telling it, but nobody's been hearing it."

The joke is that everybody in prison is innocent, so when Epps tells people he didn't kill Tomika Means, not everybody believes him. But some people do.

When Cory Epps wrote the Exoneration Initiative a letter, they listened.

"Considering how the human memory works, it's problematic when there's no other evidence to indicate guilt besides an identification," Freedman said.

The Exoneration Initiative is currently investigating new evidence, with the goal of getting Epps' case back into the court system. The group has contacted witnesses and hired private investigators to do "old-fashioned legwork," as Freedman described it. As it probed deeper into its investigation, EXI became increasingly convinced that the eyewitness misidentified Cory Epps in both the photo array and live lineups.

Freedman said the reliance on a composite sketch seemed particularly troubling, considering more than a month passed between the creation of the sketch and the identification of Epps.

"It's based on a fleeting encounter, and then no other evidence," Freedman said. "Think about how many times you walk down the street and you see someone briefly, and you could never identify them for any reason in the future."

The witness told EXI's investigators a few years ago that she stood by her identification of Epps. Dr. Mark Paoni, a criminal justice professor at Hilbert College and a former Monroe County deputy with more than two decades of law enforcement experience, said the witness identification could have been corrupted by the intense and traumatic nature of the shooting. The witness also told police she had consumed alcoholic four drinks at the bar on the night of the crime.

"To have that amount of stress, of seeing a life taken in front of you, in a dark street when you might be next and you don't know what's coming next, and it's dark out and maybe I've had some alcohol, and maybe I haven't… that's a lot of stress," Paoni said. "I wasn't there, I don't know all the particulars, but she may really believe that her statements are accurate. That doesn't mean they're right."

Epps simply believes it was a mistake by a traumatized witness.

"To have to go through that, good friend of hers, I couldn't imagine being in that same situation," Epps said. "I don't hate her. Mistakes happen. It's just that, if you know a mistake happened, you should correct it."

Tomika Means' family could not be located either, but 2 On Your Side also contacted roughly a half-dozen police and legal sources involved in both the direct investigation of Cory Epps and his trial in 1998. Sources said the witness was "adamant" in her identification, noting that she never wavered at any point during the investigation or trial. Lawrence Schwegler, the prosecuting attorney in the case, declined an on-camera interview but said he recalls it as a "hard-fought" case. Joseph Riga, the Chief of Homicide at the time, also declined an interview, as did Judge McCarthy.

"I just want them to dig deep and see the truth," Epps said. "Because these mistakes could happen to anybody."

"It's somebody's worst nightmare."

PROCEDURAL CHANGES

Two decades later, the science surrounding eyewitness procedures has changed. The Buffalo Police Department no longer allows detectives who know the suspect's identity to conduct photo arrays with witnesses, in order to avoid unintentional verbal cues that may sway the witness to pick the suspect. This past September, BPD adopted this "double-blind administration" tactic, which is a major reform effort across the country. It has been slow to catch on in some areas, according to a non-profit called the Innocence Project, but a Freedom of Information request in Niagara Falls shows that it has joined Buffalo by implementing a blind administrator policy.

In Buffalo, Chief of Detectives Dennis Richards said his department has also adopted a new photo array form based on the New York State District Attorney's Association, which provides explicit directions to witnesses before lineups.

"The process has come along over the years, to more and more be unbiased," Richards said. "In a way to not insinuate whatsoever who the investigator believes is the person who committed the crime."

This is a contrast from the investigation into the murder of Tomika Means in 1997. According to police records, the detective who conducted a photo array with the witness in July of 1997 already knew who Epps was. After she identified Epps, the records show that "this writer informs her of his name, and she states I don't know him but I've heard of him."

Richards was not involved in the Epps investigation, but in general terms, he said any comment after the identification would be unacceptable.

"Not to say you did good, not to say you did bad, not to say you picked the right guy, you picked the wrong guy, or anything like that. Nothing leading at all, even after the process," Richards said. "So the real answer on that would be that there shouldn't be any comment after other than, 'we'll be in touch.'"

In addition to the procedures, the mere fact of a one-witness case troubles some legal experts. Rebecca Brown, the Director of State Policy Reform at the Innocence Project, said that some prosecutors and police departments nowadays are uncomfortable going forward with only one eyewitness and no corroborating evidence.

"It is incredibly dangerous," Brown said. "Certainly eyewitnesses can be correct, but a lot of the time, we have very confident – but not correct -- witnesses. Obviously, a good investigation would ensure that evidence would be corroborated."

THE ALIBI AND THE OTHER SUSPECTS

The main point of evidence in the case focused on the eyewitness, but Epps' defense attorney also tried to poke holes in the prosecution's case by providing an alibi and alternate suspects. Andrew LoTempio and his team of attorneys, who represented Epps in 1998, argued that Epps was with his girlfriend – now his wife – eating breakfast at a restaurant in Amherst during the time of the shooting. Epps' girlfriend testified that she was with Epps at Perkins on Maple Road, and she provided a receipt from 5:01 a.m. on the morning of the murder. Police said the shooting happened around 4:30 a.m., so the alibi would have eliminated Epps as a possibility, the defense argued.

But the prosecution said the timeline was perhaps possible, and Schwegler told the jury that the alibi was ineffective because nobody at the restaurant identified Epps and his girlfriend, even with the existence of the receipt.

"The receipt, it tells you what they did, it tells you what they ate. Okay. Who are they? That's the question. Was he there?" Schwegler argued in court.

Epps believes the prosecution also used his prior drug conviction to destroy his credibility.

"I never had any violence on my record," Epps said.

LoTempio also questioned the police department's investigation of other suspects. On the morning of the murder, police found several suspects in cars matching the description of the car and brought them back for "show-up" identifications. The witness did not identify any of them as the shooter, but the defense argued these other suspects should have been investigated further.

But the jury didn't hear about every other suspect.

In fact, the Exoneration Initiative believes the original jury never heard key evidence, which arose in the post-conviction phase.

"It really pointed to an alternate perpetrator having committed this crime, and that's an angle we are very focused on investigating right now," Freedman said.

After the conviction, LoTempio received an anonymous letter from someone named "Pumpkin." This woman told LoTempio that she knew who the real killer was— a "cruel and heart less man who have to be stopped (sic)." Police had interviewed this woman after the murder of her boyfriend, and she claimed in an appeal that she told the officers that the man who killed her boyfriend also admitted that he killed Tomika Means. The man was eventually convicted of the other murder and is now in prison. Police, however, testified they had no record of "Pumpkin" providing this information during the other murder investigation, and the judge eventually denied Epps' appeal.

"Whether or not she told police, it does appear the person she told police killed Tomika Means, killed Tomika Means," Freedman said. "I think there were enough people that knew he did it, that a little more investigation could have narrowed the field a little more, and his photograph could have been put into an array and done a lineup."

"Unlike the case against Cory, there would have been evidence out there to corroborate an identification of him based on a composite."

![Anonymous Letter[ID=5839435] ID=5839435](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/4044b1e7645488621f157de466cf1a990870caa2/r=500x333/local/-/media/WGRZ/GenericImages/2014/02/26/1393443367004-anonymous-letter.jpg) Freedman said the man they believe committed the murder looks similar to Epps. According to records obtained by 2 On Your Side, the witness to Means' murder admitted to a private investigator that this alternate perpetrator had a "definite similarity" to Epps.

Freedman said the man they believe committed the murder looks similar to Epps. According to records obtained by 2 On Your Side, the witness to Means' murder admitted to a private investigator that this alternate perpetrator had a "definite similarity" to Epps.

"But the composite sketch is vague enough that it could be either of them, or countless other people. And that's the danger of a composite sketch, because the witness is comparing them to the composite sketch, and not necessarily to their own memory," Freedman said.

Epps didn't want to publicly share his theory on an alternate perpetrator.

He said he's just concerned with clearing his own name.

"I don't believe the Exoneration Initiative takes on cases it doesn't believe in. I believe God's got his hands on me," Epps said. "It's time for me to get out of here."