ALBANY, N.Y. – Carl Paladino’s lawyers presented a final legal defense on Wednesday as they fight to preserve their client’s elected Buffalo School Board seat, the fate of which now rests in the hands of the state education commissioner after the conclusion of a five-day removal hearing.

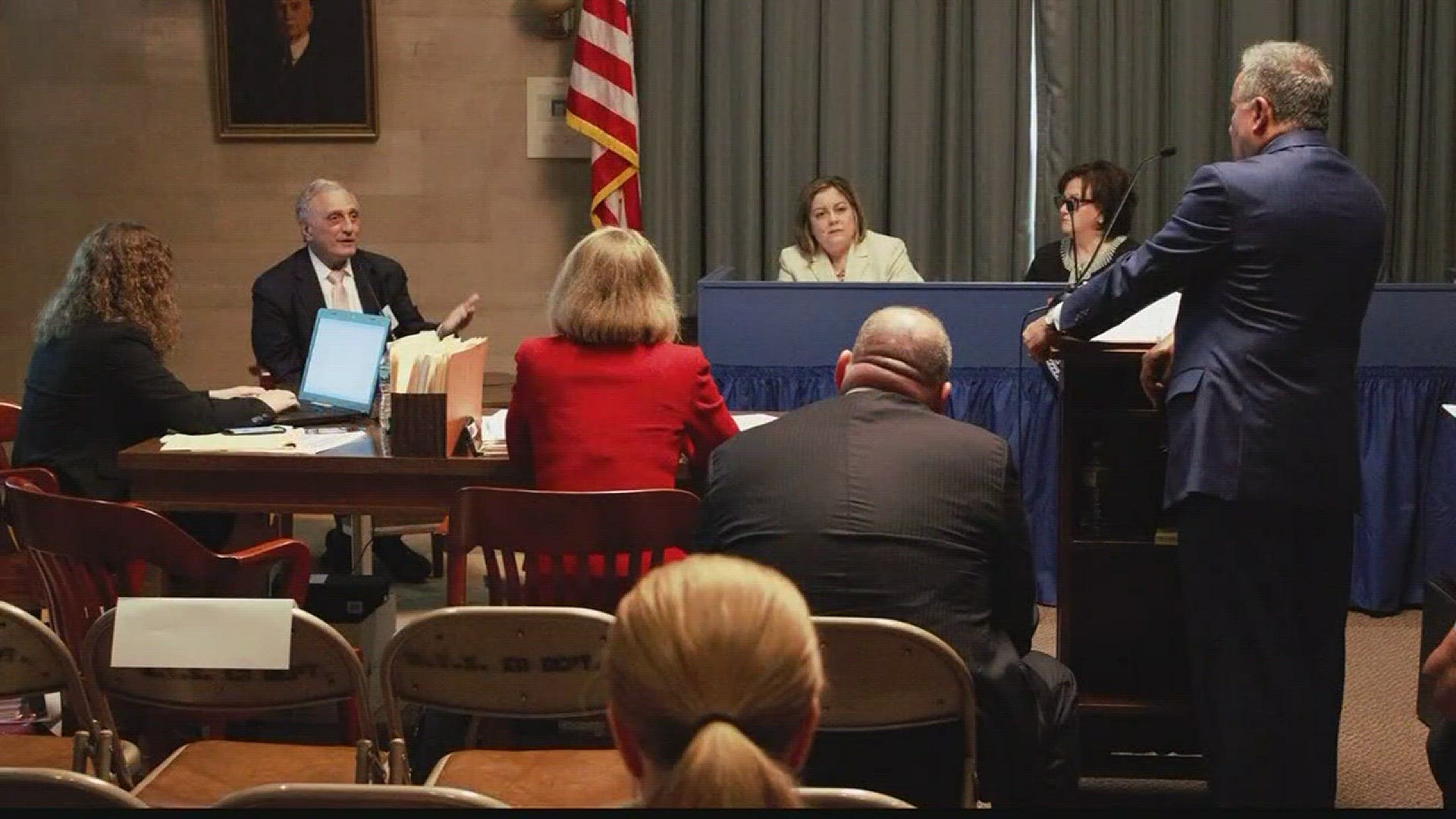

These proceedings – the first of their kind in the history of public education in New York – included more than 20 hours of testimony from 10 different witnesses, all culminating in Wednesday morning’s closing arguments in the Regents Room of the State Education Department building on Washington Avenue.

State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia will now review the case before issuing a written ruling on the petition filed by six school board members, who are seeking to boot Paladino from the school board over allegations of illegal disclosures of sensitive district negotiations.

Dennis Vacco, the legal counsel for Paladino and a former New York State Attorney General, said in his closing argument that he does not believe the petitioners met their burden of proof during the hearing. He once again painted the board majority as having a vendetta against Carl Paladino, accusing them of manufacturing a phony argument about illegal disclosures only after learning they didn’t have a legal case to kick him off the board for his racist statements about the Obama family.

“As offensive and low as those statements were, they are constitutionally protected. The petitioners only reluctantly came to accept that fact,” Vacco said, referring to the comments published in the Dec. 23 article of Artvoice. “The petition must be dismissed. And the removal of a duly-elected board member must be denied.”

On the other side, the board majority’s lawyer, Frank Miller, delivered a narrow closing argument focused on allegations of illegal disclosures from executive session negotiations about the teachers’ contract and other litigation. Miller argued that Paladino’s comments, including an editorial written in Artvoice on Jan. 5, caused “real, measurable harm” to the district by revealing confidential information about the contract negotiations, such as the superintendent’s reaction to the possibility of a teachers’ strike.

Miller argues that any union will be able to use the information revealed by Paladino against the district in the future, and he urged Commissioner Elia to ignore Paladino’s claims that the board majority is retaliating against him because of his racist speech.

“What a notion. What an idea, that you can make comments that are so beneath contempt, so offensive, and then turn around and have a license to say and do whatever you want because you can wrap yourself in the cloak of the First Amendment,” Miller said. “The First Amendment was not designed to give people license to commit violations of other laws.”

Commissioner Elia said Wednesday her office will accept post-hearing briefs and responses through July 19, meaning a decision on Paladino’s future may not come until at least August. After five days of hearing room clashes, though, both sides’ arguments have already been well-established.

Vacco has consistently argued that Paladino’s disclosure of information about contract negotiations served a public interest for taxpayers and voters. Paladino had harshly criticized the terms of the deal with the teachers' union, claiming the new contract would cost too much and deplete the district’s reserve funds.

It was for that reason, Vacco argued, that the public deserved to know how and why the contract was negotiated.

"There is a real and meaningful public impact of deficit spending," Vacco said. "This is a matter of intense public interest."

After Wednesday’s arguments concluded, Paladino himself addressed the media and emphasized the same concept. He specifically defended one of the comments he made in the Jan. 5 editorial about Superintendent Kriner Cash panicking at the possibility of a teachers’ strike.

“It’s my belief that the public has a right to know,” Paladino said, “that their negotiator is weak, is panicking, is irresponsible.”

Miller, however, has contended that these kinds of comments from Paladino place the district at risk in the future, not only with the teachers’ union but with any collective bargaining negotiation the district may encounter. He also forcefully rejects the illustration Vacco painted of Paladino as a public servant who was looking out for the interests of his constituents. In a heated exchange on Tuesday, Miller repeatedly pressed Paladino on the witness stand about why he felt he had the authorization to disclose information from an executive session, no matter his feelings about the terms of the teachers' contract.

Miller also introduced a new argument during Wednesday’s closing argument, drawing attention to Paladino’s testimony about Artvoice allowing him to publish the Jan. 5 article about the teachers’ contract to apparently make amends for the previous Obama comments on Dec. 23. Miller told Commissioner Elia this evidence stood as proof that Paladino willfully violated board policies regarding confidentiality, in order to further his own personal agenda.

“It, in effect, gave him a platform to redeem himself, to essentially exonerate himself or clear himself or whatever his mission was, when he could write another article to make sure the public knew he was a good guy,” Miller said. “It was clearly written not in response to – but as a result of – the Dec. 23 Artvoice comment.”

In the interviews after the hearing, Paladino shot down a question asking him about Miller’s latest argument. “You know me better than that,” he said.

One of Miller’s clients, Board President Barbara Seals Nevergold, also addressed the media after Wednesday’s proceedings.

Nevergold, who testified for five hours last week, made the case that Paladino’s disclosures severely hampered the board’s ability to conduct its business.

“To have confidence that information will not be disclosed without permission of all board members is crucial to the function of the board,” Nevergold said. “This is the reason we brought the case.”

Paladino and his attorneys, who have also filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the district and the six board members seeking his removal, would not say whether they would pursue legal action if Commissioner Elia chooses to strip his seat on the board.

But Paladino’s suit in federal court alleges violations of the First Amendment based on his perception that the board majority retaliated against him for his Obama comments.

“I was wrong, and I said that, and I was done with it then,” Paladino said, “although they weren’t done. Because now they wanted to use that to remove me.”

Nevergold did not hide the fact that the racist comments bothered her.

But, like her attorney has told the commissioner five days in a row, she noted that the petition makes no mention of those comments.

“Everyone was very upset about it,” Nevergold said, “but that did not mean that when we saw the articles and what he revealed and disclosed in those articles that came out of executive session, that we should not have followed up and really brought this case on that basis.”'

For a detailed play-by-play of Tuesday's proceedings and Paladino's testimony, see below:

9:05 a.m. Witness #9: School Board Member Larry Quinn

Larry Quinn, who has aligned himself on the school board with Paladino, took the stand first on Tuesday. In response to questions from Jennifer Persico, one of Paladino's attorneys, Quinn described his experience in collective bargaining negotiations, particularly his experience working with the Buffalo Sabres and the National Hockey League.

Quinn testified that when he ran for school board in 2014, he was well aware of the political influence of the Buffalo Teachers Federation, which strongly opposed his candidacy. When he first took office, Quinn said he encouraged former superintendent Donald Ogilvie to restart negotiations with the union about the teachers' contract. When Kriner Cash became the superintendent in 2015, Quinn said the two seemed "completely aligned" on their mission as it related to the negotiations with the district's legal counsel.

Quinn said there were "renewed efforts" to continue negotiations when Cash took over as superintendent. He then accused the union of stalling the talks, adding that there didn't appear to be any "formal negotiations" like he was used to in his business and development experience.

In 2016, when union-backed board members became the majority through the latest round of elections, Cash decided to forgo the legal counsel and begin negotiating on his own, Quinn said.

When talks began to heat up that fall, Quinn testified that there was "clearly" a sense that the Buffalo Teachers Federation could go on strike-- something that was referenced by Paladino in the Jan. 5 Artvoice article that serves as the basis of his removal petition.

Persico then asked Quinn about an Oct. 12, 2016 school board meeting. This was the final meeting before the district reached an agreement with the teachers' union about a new contract. It was also the meeting that included the executive session of which Paladino is accused of later releasing confidential information.

Quinn testified that Kriner Cash asked during executive session whether the district should offer an additional $10 million as a part of the proposal to the union, which would support another reference Paladino made in the Artvoice article.

Quinn then said he discussed the $10 million with Cash. Although he wasn't necessarily opposed to offering more money, Quinn said he wanted to make sure the district was getting a strong deal in return for the additional money. He testified that he then called Carl Paladino and asked him what he thought of the proposal. The $10 million figure was "sort of assumed at that point," Quinn said, which would support Paladino's legal argument that these negotiations were imperative for public consumption.

Quinn said he became aware that the BTF had published some collective bargaining agreement information on its website that weekend. He was then informed of a special meeting set for Oct. 17, 2016, for the purpose of approving a deal for the new teachers' contract.

Quinn was then asked about the Oct. 17 meeting. He said he objected to the executive session that was called during that meeting, calling it "critical" for the discussions to happen in public view.

After a two-hour executive session -- which Quinn and Paladino decided not to attend -- the full board then voted to approve the new contract. Quinn testified there was "no presentation" or discussion in public session about the terms of the deal. Quinn said he attempted to ask questions after the executive session, but he did not get the sense that other board members were interested in listening to his perspective.

Persico then introduced a video from the Oct. 17 meeting, which showed Larry Quinn objecting to the executive session. Quinn said he felt strongly that the "public needs to know" about these discussions. In a second video, you can hear Sharon Belton-Cottman -- a board member who testified last week -- saying that the negotiations were sensitive and could not be jeopardized by discussion outside of executive session. In another video, you can then hear Paladino forcefully objecting to the executive session as well, arguing that the negotiations should also be made public ahead of the vote.

In testimony, Quinn then voiced his objections to the cost of the teachers' contract. He has long argued that the deal harms the district's finances and forces it to use too many reserves. This testimony continues to set up Paladino's overall argument-- that the deal wasn't good for taxpayers and needed to be discussed publicly.

Persico then decided to address Paladino's comments in a December article of Artvoice, in which he made racist comments about the Obamas. She's beginning to set up the other argument here-- that the board majority is acting against Paladino in retribution.

Quinn said he did recall the meeting on Dec. 29, in which the board majority demanded Paladino resign or else they'd seek legal counsel to start the removal petition process. Quinn, who voted against that resolution, said he was "was very offended by what Carl said" but that he wanted to give Paladino the chance to atone for his mistake. Quinn wanted Paladino to explain himself and apologize directly to staff and students in the district. Quinn said he did not, however, support the effort to remove a public official from his elected position.

A week later, when the board voted to hire Frank Miller as their outside counsel, Quinn said he wasn't initially interested in meeting with Miller. However, the two did ultimately meet in early January. Quinn testified that Miller told him the board could be liable for a lawsuit if they pursued removal based on Paladino's remarks about the Obamas. Miller, according to Quinn, was "not too thrilled" with the approach of asking for Paladino's removal because of offensive speech.

Testimony then began to focus on an informal Jan. 17 board meeting, which Quinn claims he was not invited to. Last week, Board President Barbara Seals Nevergold testified that only board members who voted for legal counsel had been invited to attend. Quinn accused her of calling an improper meeting. This is important because one day later, the board voted to file a petition for Paladino's removal.

Quinn said he was not aware the board majority would pursue a case against Paladino based on allegations of confidential disclosures. He testified he only became aware of this on Jan. 18, when the resolution to file the petition was passed.

Persico asked Quinn if there was any authorization by the board to "switch gears" from investigating the Obama comments to investigating the allegations of confidential disclosures. "No," Quinn testified, adding once again that he was not aware of the board's pursuit of these allegations. Quinn then described how Paladino was served with legal papers during the Jan. 18 meeting. Persico has consistently questioned how the legal papers were served so quickly.

At 10:30 a.m., Persico's line of questioning ended.

10:50: a.m.: Cross-Examination of Quinn

Frank Miller's associate, Christopher Millitello, conducted the cross-examination of Larry Quinn. The Paladino team had objected to Miller's office cross-examining Quinn -- since they believed there was a conflict of interest, considering they represent the board -- to which Miller said he was being "smeared," "slandered" and falsely accused of unethical conduct. Commissioner Elia sided with Miller and allowed the cross-examination to continue.

Militello immediately turned his focus to the Oct. 12, 2016 board meeting. He played a clip of the meeting on the video board, in which Quinn made a motion to go into executive session. Quinn testified that he did not raise any concerns about going into executive session at that time.

Quinn admitted in his testimony that it appeared Carl Paladino did refer to the executive session negotiations in the Jan. 5 Artvoice article. Militello asked Quinn to read a passage from the article, in which Paladino had written about the executive session discussions and the possibility of a teachers' strike.

Militello pressed Quinn on whether he believed a strike was illegal-- the point of this questioning appeared to be to press him on why Paladino felt he could release such information in a public media outlet. Quinn testified that he did not believe the Artvoice article was the only source for the public to understand these negotiations or the possibility of a strike. Quinn said there was already "speculation" published in media reports.

Quinn said that he believes that the information Paladino revealed was only confidential during negotiations, but that it would be allowed for public assumption once the matter had been settled. Although he admitted he is not a lawyer, Quinn testified that there was no explicit direction to protect the executive session negotiations that Paladino addressed in his editorial.

Militello then entered the Code of Conduct into evidence and asked Quinn to read part of it. Quinn was instructed to read Page Nine about confidentiality requirements, which said, "no board member or employee shall disclose confidential information... to further their personal interest or interest of anyone in his or her family." The board majority is accusing Paladino of violating this particular code of conduct.

Militello then recalled the video Paladino's lawyers played of the Oct. 12, 2016 board meeting, in which Quinn and Paladino objected to an executive session while board member Sharon Belton-Cottman said the teachers' contract negotiations needed to remain private and confidential. Militello appeared to be establishing that all board members needed to follow the code of conduct-- and that Belton-Cottman was perhaps following the guidelines unlike Paladino.

Militello then returned to the Jan. 5. Artvoice article. In response to harsh questioning, Quinn testified that Paladino did appear to write about the discussions that took place in executive session. However, Quinn pointed out that Paladino's editorial didn't refer to comments made by any other board members.

Quinn testified that because he believes the teachers' contract information had already been posted by the BTF itself, he also believed the October discussions of the contract should be held in public view as opposed to private executive session.

11:30 a.m.: Redirect of Quinn

Jennifer Persico and Paladino's legal team had a chance to respond to the cross-examination. Persico asked Quinn about the October meeting in which board member Sharon Belton-Cottman had said teachers' contract negotiations needed to stay private until an agreement was reached. Quinn was once again asked to reach the code of conduct about what school board members can and cannot disclose from executive session. Quinn said it was his understanding that the passage meant a board member couldn't use executive session information for his or her own personal gain. That's different than the board majority's lawyer's interpretation, which seemed to suggest that a board member could not disclose any information whatsoever."

In a follow-up question, Militello asked Quinn if there was a difference between the content of the teachers' contract itself and the discussion of the contract. Paladino's team objected to that question and Elia agreed it could not be asked.

11:40 a.m. Witness #10: Carl Paladino

Responding to questions from his attorney, Dennis Vacco, Paladino described his work and life experience, including attending St. Bonaventure and Syracuse and serving in the military. After practicing law, Paladino said he began to enter into the world of development in pursuit of a more fulfilling career. Although Paladino's son is now the CEO of Ellicott Development, he said they essentially act as "one person" when it comes to decisions about running the company.

Paladino then began describing how he decided to run for governor in 2010. Although Paladino lost in a landslide to Andrew Cuomo, Paladino said he believed he'd still gotten his message across. Three years later, Paladino ran for the Park District seat on the Buffalo Board of Education.

Paladino said he decided to run for school board because he believed the Buffalo Public Schools were the "one most pathetic thing" holding the city back in terms of development and economic progress. He said he witnessed "nonsensical, power-hungry" attempts by people in power to keep the status quo, and he said the district was full of "corruption." These are familiar attacks from Paladino, who has frequently accused his opponents on the school board of being resistant to change. Paladino even referenced former superintendent Pamela Brown during his testimony, referring to her as "that Brown woman." He called her a "placeholder" superintendent and used her as an example of perceived dysfunction.

When Paladino took office in July 2013, he said there was not a single school board member who aligned with his views about how to improve the school system. Paladino recalled that three of the current petitioners -- Barbara Seals Nevergold, Theresa Harris-Tigg and Sharon Belton-Cottman -- were on the board at that time as well.

Eventually, Vacco turned to more direct questioning about the teachers' contract negotiations. Vacco asked about the state of the negotiations in 2013, when Paladino first took office. He testified that the union appeared to have full control of the process. Paladino testified that although he respected some of Buffalo Teachers Federation President Phil Rumore's accomplishments, he did not personally get along with him. He called Rumore, who testified last week, a "schemer."

Paladino then began testifying about the school board elections in May 2014, when Paladino believed he'd finally won a majority. He testified about the teachers' contract negotiations and how it was still a high priority for the district to finally reach a deal with the teachers' union. It appeared Vacco and Paladino were beginning to establish the critical public importance and high stakes of the teachers' contract negotiations, which is really the heart of the entire petition asking for his removal.

Paladino said that when Dr. Kriner Cash was being considered for the superintendent position, they enjoyed dinner together along with board member Larry Quinn. Paladino said he needed his assurances that Cash would understand how important it was to get a contract with the teachers-- but more importantly, how important it was to get a "good contract" with the teachers.

"We couldn't afford a giveaway," Paladino said.

Paladino said he'd talked to Dr. Cash about the need to cooperate with the legal counsel to finally reach a deal for a new teachers' contract. Paladino also testified that he talked to Cash about the role of charter schools and pressed him on whether he understood the difficulties of the superintendent position in the Buffalo Public Schools.

Paladino, who was not in town for the school board vote to approve Cash as superintendent, testified that he would not have voted in favor of Cash's appointment. He praised Cash for some of his personal qualities, but "I didn't see him understanding the nature of our board," Paladino testified. "And the fact that he would have to deal with very onerous people who had different agendas. They had a friends and family agenda." Paladino specifically said he didn't believe Cash had the right qualities to negotiate with Rumore and the Buffalo Teachers Federation.

Paladino then testified that he'd identified a "scheme" carried out by Rumore during the negotiations. Paladino continued to comment on his uneasiness with the negotiations and his lack of faith in Cash, who had shunned the legal counsel in May of 2016 to become the chief negotiator. Paladino had lost his majority in the May 2016 school board elections, which he seemed to blame on the teachers' union. Paladino also blamed the influence of rival developer LPCiminelli, which Paladino and his previous allies voted to sue over the joint schools construction project.

Before the new board was sworn last year, Paladino testified that the previous legal counsel was dropped by Dr. Cash "without any consultation." This appeared to bother Paladino, who believed this threatened his ability to lend a voice to the contract negotiations. He also testified that he believed the decision to drop the counsel was probably made by Board President Barbara Seals Nevergold, not necessarily Cash himself. To Paladino, this was proof that the union had intervened in the teachers' contract negotiations.

Paladino explained that he believed he could now see the whole scheme: Rumore and the BTF had pumped money into the elections in May 2016, and suddenly they had leverage over the district in contract negotiations. That''s how Paladino saw it, at least, according to his testimony.

After a break, Vacco turned the focus to the Oct. 12, 2016 school board meeting, which occurred five days before the teachers' contract was formally approved. In his testimony, Paladino recalled a "deceptive" presentation given by Phil Rumore, which he felt did not accurately reflect the total cost of the proposed teachers' contract. Paladino also recalled attending the executive session on Oct. 12, when the status of the negotiations was discussed. Vacco asked if there was any discussion of "future strategies" for dealing with the Buffalo Teachers Federation, to which Paladino responded "yes." They had discussed how much more money could be authorized as a part of the contract, Paladino said, which was included in the Artvoice article in Jan. 5.

Paladino then discussed a "board retreat" held a few days later, which took place at the Delaware North building on Delaware Avenue in downtown Buffalo. Vacco asked him if he'd gotten a call from Larry Quinn that day. Paladino said he had-- and that he'd told Paladino that Kriner Cash wanted to offer more money to the union for the teachers' contract. This is the conversation Quinn had described in his own testimony on Tuesday morning. Paladino said he was OK with offering more money, as long as the district got what it wanted in return.

Paladino said he was aware on a "day-to-day" basis on everything that was happening with that contract. He said these details and the contract negotiations were discussed in "open meetings."

"There was no grand secret about these negotiations," Paladino said.

Paladino then testified that during the Oct. 12 meeting, legal counsel had not given any advice. He also said that he believes the executive session did include discussion of a potential teachers' strike-- and that he specifically asked Cash about a strike because he felt it was illegal under the Taylor Law. Paladino wrote about the possibility of a strike in his Artvoice article on Jan. 5. Paladino testified that he was aware that the Buffalo News Editorial Board had met with Kriner Cash in the fall, and he was aware that Cash was quoted as mentioning preparations for a teachers' strike.

Vacco asked Paladino when he first became aware that the union had reached an agreement with the district. He testified that he had received notification of a memo that weekend, informing him of a meeting scheduled on Monday.

During that Monday meeting, Paladino recalled that the teachers' contract was addressed immediately. It was completed, Paladino remembered learning, and the board then voted to go into executive session. "I totally disagreed with that," Paladino said. "I was elected by many good people, because I'm a forthright person and I know my responsibilities and they know I work very hard at what I'm doing. And I thought it would be so insulting for us to take on the biggest challenge that we take on as a board -- ever -- and not keep them informed, or inform them of what we see as individuals. People elected me because I can see things other people can't see. I can do things other people can only think of doing. I'm bold and I'm very direct in that sense. And in good faith, I think people have a right to know what we are doing before we do it."

Paladino recalled that he did not attend the executive session on Oct. 17. It lasted about two hours, he believed, but he was not at any point given any documents that explained the terms of the teachers' contract.

During this executive session, Paladino said he still had no idea how much additional money Dr. Cash had offered to the union for the new contract. It was at that point that Paladino finally saw the document about the terms of the agreement.

But in his testimony, Paladino complained that he and board ally Larry Quinn did not have much time to voice their objections at the meeting prior to the vote.

"The biggest issue we ever encounter, and they give us 15 minutes to answer questions," Paladino said. "They're all sitting there real smug and they voted in favor of it."

But the bottom line, Paladino said, was that the teachers' contract cost too much and ate up too much of the district's reserves. And Paladino continues to testify that he does not believe he was ever given the chance to put up a fight against the contract, which begins to set up his argument that his Artvoice disclosures were necessary and in the interest of the public.

"They'll just keep letting this nonsense go on, and on, and on... this contract should never have seen the light of day," Paladino testified.

Paladino said he had no personal gain in the contract -- and no personal gain in releasing details about the contract -- which is an attempt to show that perhaps Paladino may not have violated the code of conduct for board members. Expect Frank Miller to dispute that.

Vacco then turned his attention to an executive session called during a meeting on Dec. 21. Paladino said the motion was made to go into an executive session without specifically citing the purpose, which has been a point of contention from Paladino's team throughout the hearing.

Vacco then presented Paladino with a Dec. 22 email that Paladino sent to Board President Barbara Seals Nevergold, regarding "superintendent evaluation." Paladino testified that nothing in the email appeared to reference anything from an executive session. His email was harshly critical of board majority members and the Ciminelli deal, but Paladino testified that none of these topics had been discussed in the board meeting the night before. These emails are a part of Frank Miller and the board majority's case, so you'll expect to hear a much different story when cross-examination begins.

Overall, Paladino seemed to strongly deny that the Dec. 22 email had released any unauthorized information about the executive session held the night before.

Vacco asked Paladino, "Why do you think we're here?"

Paladino responded: "I don't represent the status quo. I was elected on a platform that was gonna fight the status quo and provide a better education for all the children of the city of Buffalo... I believe in education. And I believe also in certain things in government, especially honest judgment, character, integrity, doing the right thing and I find people with very deceptive and diabolical agendas, have controlled our education system for a long time. And that is the reason we have such dysfunction in our traditional public schools, so I began to expose that right from the beginning, I formed my own agenda.. they fought me all the way on every question I had, they denied me seconds, denied me an opportunity to even read out loud my motions.""

"They didn't want anybody to expose the underbelly of this beast. And from my perspective, that became my challenge and I fought it all the way. I'm the one who exposed the Ciminelli mis-allocation of funds. I'm the one who exposed many, many of these issues that in my efforts, have shined a light on incompetency, shined a light on procedures that are wrong."

Vacco then asked Paladino what happened the next day, on Dec. 23, when Paladino's racist comments were published in Artvoice.

Paladino said the following: "There was no excuse for me thinking the way I was thinking in that moment. I was thinking about Obama and his wife and my thinking got carried away... it was a "terrible error to allow that message to go public. And I sincerely regret my words. I regret thinking them and saying them."

Paladino said if he had a chance to take the words back, he would. He agreed with Vacco that it has hampered his ability to conduct business as a school board member. "And you regret that?" Vacco asked. "Yes," Paladino responded.

Paladino said he was aware of the backlash over his public comments, but he'd planned a trip out of town for the next week and a half after the Dec. 23 article was published. He was not present on the Dec. 29 special board meeting at City Hall, which was called in response to his comments about the Obamas. However, Paladino testified that he was fully aware that the board voted in favor of a resolution demanding his resignation or else they'd begin to seek his removal with the state.

Paladino, of course, did not resign. He returned to town a few days after New Year's, but he did not attend a Jan. 4 special meeting because he said he "didn't know about it."

Paladino testified that prior to the filing of the removal petition, he was never criticized or called out for any allegation of disclosing confidential information in the Dec. 22 email.

It was only until after the Jan. 5 Artvoice editorial -- the one about the teachers' contract negotiations -- that Paladino heard he may face action for disclosing information. But he totally disagreed with that allegation.

"I have every right to expose a rigged contract," Paladino said.

Paladino then testified about his recollections of the interacations and meeting with Frank Miller, the attorney hired by the board majority to pursue the removal petition. Miller told Paladino he was investigating the remarks he'd made in Artvoice, according to Paladino.

Paladino said Miller then came to his law firm to meet. "He was investigating my Obama words," Paladino remembers understanding. Paladino said that Miller had concluded that his words were protected by the First Amendment. Vacco asked Paladino if he understood the Dec. 29 resolution to be illegal-- Paladino testified that was his understanding as well.

Paladino said Miller also asked him about the Artvoice editorial he wrote on Jan. 5, in which he had heavily criticized the teachers' contract and made references to executive session conversations. "This article came about as a result of my distress with the publisher, who had been a friend... over printing my words on Dec. 23."

Paladino continued to testify that he was told by the Artvoice publisher that he would be offered an opportunity to speak his mind. This, essentially, seemed to be Artvoice's way of giving Paladino a chance to atone for his mistake.

Paladino said his intent in drafting the editorial was to expose the intent of the contract and the "rigged" nature of the negotiations. He then testified that he published the comments in "good faith" for the public interest and did not have anything to gain personally from releasing the information.

"They had a right to know the scheme that was put together and the rigging of this contract," Paladino said.

Paladino then testified that many other comments he made in the Jan. 5 editorial in Artvoice were not discussed in any executive session with the board.

After a long discussion of Paladino's comments about negotiations and other district information, Vacco then moved to what he called the "last act" of his questioning: the Jan. 18 meeting in which the board majority voted to file a petition for Paladino's removal.

Paladino testified that he was not invited to the Jan. 17 informal meeting, which Larry Quinn also testified he was not invited to. Vacco's argument is that this informal meeting led to the resolution the next day.

Paladino testified that he was not aware of any formal meeting between Jan. 4 and Jan. 18 in which the petition was changed to focus on his alleged confidential disclosures.

3:30 p.m. Cross-Examination of Paladino

Frank Miller began his cross-examination by asking Paladino about their Jan. 10 meeting, when Miller was retained by the board to seek his removal petition. Paladino recalled that meeting and had previously testified about it earlier in the afternoon.

After discussing the attorney/client privilege justification for executive sessions with Paladino, Miller then introduced a document explaining how an executive session can be conducted. "Do you agree with me, sir, that there is no indication there about a time limit as to any duration about confidentiality?" Paladino simply said there was no way of knowing, since no such information was listed. Miller asked Paladino if he knew of any executive session law being abused on Oct. 12, 2016, when the board discussed the teachers' contract negotiations. Paladino testified that he did not object to that executive session at the time.

Miller then asked Paladino if he was familiar with the code of conduct. Paladino said he'd read part of it, but "I haven't read the whole thing," he said. He did not recall the code of conduct when prompted. Miller then instructed Paladino to read a passage from the code of conduct about prohibitions on releasing executive session information for personal gain. Paladino strongly denied that his reform agenda as a school board member could be classified as personal gain.

Miller then asked Paladino if he was aware of a policy prohibiting disclosure when he wrote his Jan. 5 article. Paladino said he was "not specifically" aware of the policy at the time, although he had admitted it was his responsibility to be aware of those types of things as an elected school board member.

Miller was extremely narrow and focused in his line of questioning, presenting policies and procedures that prevent a board member from being able to disclose information from private executive sessions. Paladino began to argue in a heated moment that he believed he could disclose the information as long as it had been discussed in other public discourse.

"Do you get to define as an individual, what you consider to be confidential from an executive session? Yes or no?" Miller asked. Paladino responded that no, that is not his job, but instead it is up to the law.

"Can you cite to me a law, rule or regulation that indicates an executive session privilege evaporates after collective bargaining finishes?" Paladino responded it was his duty to his constituents as an elected official... "It's inferred," Paladino said. "Tell me where it's stated."

Miller then asked Paladino read another rules document, to which Paladino read: "matters discussed in executive session must be treated as confidential that is never discussed outside of that executive session."

Paladino argued that he did not disobey any policies, to which Miller continue to press him about whether he intentionally ignored them. After some heated exchange, Miller asked, "Are you telling this commissioner if you disagree with a board policy, you can disobey it?" Paladino said that if it's too vague, then yes, he could argue that policy.

Paladino then testified that his Artvoice comments about Dr. Cash seeking an additional $10 million did indeed come from an executive session. Miller pressed Paladino about whether this could give the union leverage in future negotiations, to which Paladino strongly denied.

Paladino became very upset with Miller's line of questioning about whether the disclosures were illegal from the executive session. Miller insinuated that Paladino could have made his point perfectly clear about the teachers' contract using publicly available information, as opposed to the private negotiations. Paladino clearly disagreed with that: "If what was discussed was part of a larger scheme, I believe you have to fill in the entire context," Paladino testified.

Miller asked Paladino if he had any evidence of actual rigging of the teachers' contract. Paladino testified that he has not contacted any police agency or even made a complaint about alleged rigging or other illegalities.

But Paladino continued to argue that the public needed the whole context of the negotiations, as opposed to just the total outcome.

Miller then pressed Paladino about his allegations of "criminal activity" regarding the collective bargaining agreement, and Paladino admitted in testimony that he had not filed any official complaints related to that allegation.

Miller shifted focus to Paladino's discussion of the LPCiminelli litigation. "Did you have authorization or permission from the Board of Education to release any information from that executive session?" He was referring to a session on Dec. 21. Paladino said that he did not have any authorization, but he did not believe his disclosures made any reference to that executive session. Miller said that claim was false.

Later, Miller went to the tape of a school board member on Dec. 21 to show that Paladino hadn't objected to the calling of an executive session. Paladino testified that he has long been on the record as saying the board holds too many executive sessions, even though he did not specifically object that day.

Miller went back to the teachers' contract: Wasn't it public record once it became an official agreement? Paladino said it would have been too late at that point for the public to change anything.

"The people had a right to know that and they weren't going to see if it was only discussed in executive session," Paladino said.

Miller then questioned why Paladino skipped the Oct. 17 executive session, right before the board voted to approve the teachers' contract. Miller had to persistently ask this question several times. Paladino said he still believed the contract was "rigged," even though he hadn't seen the final terms of the deal.

Miller asked Paladino if he wrote his Jan. 5 Artvoice article because he'd thought the contract was "rigged." And he asked Paladino if that gave him an argument to release the information. Paladino responded, "yes."

Miller said those were all the questions he had.

Vacco then decided to take over for a few additional questions. He introduced the board policy once again, asking Paladino whether he believed a policy was the same as a "statute." Paladino said he didn't think it did. Paladino also testified -- once again -- that he did not believe he had anything to gain personally by writing about the teachers' contract negotiations.

Miller had one final question, asking Paladino to read a definition of the interpretation of "confidential," in which a state education commissioner had said "confidential" was too narrowly defined. Miller asked Paladino: "isn't it correct" that any education law interpretation comes from the commissioner? Paladino said it comes from the legislature.

Then, Vacco had one final question, actually: had Paladino seen a document about legal issues board members might encounter? "Do these sections under duty of confidentiality give you any further clarification about what's confidential and what's not?" Paladino responded, "no."